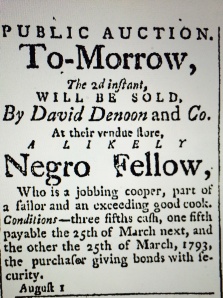

City Gazette and Daily Advertiser (Charleston), Aug. 1, 1791

During orientation at Mystic Seaport in April Voyagers were told that hot cooked meals would not be provided when we sailed on the Charles W. Morgan. Being polite well-behaved academics, artists and writers, we did not harrumph about the cold provisions we were to be provided. Why complain when we were being given an opportunity few others would ever have, to sail on America’s oldest whaling ship. This would not, however, have been the reaction of seamen in the Age of Sail to such news.

As Samuel Pepys, Secretary to the Admiralty, observed in 1677, “Englishmen, and more especially seamen, love their bellies above everything else.” The importance of food in seamen’s lives was no less important in the eighteenth century. Which raises the question, who were 18th century ship cooks?

As the above slave sale notice implies, black men such as the “Negro Fellow” being sold, worked both as sailors and cooks. Many of these men could regularly be found working as ship cooks in the Age of Sail. But if so, which blacks became ship cooks, and why were there numerous black ship cooks, and what was the role of black cooks at sea?

To understand the place of black cooks it is important to consider who became ship cooks and why. Throughout the Anglo-American maritime world disabled and elderly men were employed as cooks. (The vessels of Scarborough, England in the mid-eighteenth century are a good example of this practice. See”Sewing a Safety Net,” http://thekeep.eiu.edu/history_fac/13). A primary reason for disabled and elderly men being employed as cooks was the job being far less physically demanding than the hauling of lines and unfurling sails that most seamen did.

Men missing a limb or having impaired vision were believed capable of being cooks and frequently were so employed. Thus, in 1753 when the cook of HMS Jason deserted in Boston, the ship’s captain saw little reason not to hire as the deserter’s replacement, William Hallbrook, a seaman who had lost a leg in the naval service. Musters of naval ships throughout the Atlantic contained entries for scores of other naval seamen who having lost limbs in action were kept in service as cooks. As one sailor so aptly observed, many seaman had a bullet “shot away one of his limbs, and so cut him out for a Sea-Cook.” While one would think having sight would be a bona fide occupational qualification as a cook, one-eyed men and even those who were blind, such as men on HMS Sovereign in 1741 and HMS Flora in 1771, were employed as cooks. The prevalence of disabled cooks is made apparent by the Navy Board’s 1746 pronouncement that there were no vacancies for cooks “because so many crippled sailors have been helped this way” and its 1776 order directing “cripples and maimed persons as are pensioners” be given preference for appointment as ship cooks.

Another group of men regularly employed as cooks were older men. In the eighteenth-century men over the age of forty generally only went to sea as non-officers if impoverished or without other opportunities. However, ‘old’ men (forty or older), frequently served as cooks on all types of ships. Most of these old cooks were not quite as elderly as Nicholas Dougherty, the eighty year old cook on HMS Eagle. But forty and fifty year old cooks were commonplace on ships in the Age of Sail. The Charles W. Morgan itself is a good example; at least two of the six cooks whose age were noted in the ship’s crew lists –John Branscombe of England and Felix Morris of Chile — were forty years of age and older. Each of these men made multiple voyages with Branscombe serving on five consecutive year long voyages.

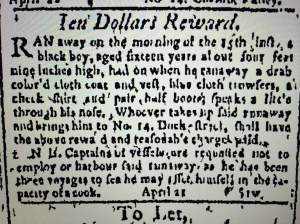

As my last blog post discussed, ship captains were often willing to hire runaways with or without maritime experience. Often these fugitive slaves found work on ships as cooks. For example, when the 17 year old South Carolinian waiting boy Tom fled in 1797 the young bondsman was believed to have sought a berth as he had previously “shipped himself as a Cook.” John Giff and other fugitives “offered [themselves] as Cook[s] on board some Ship” or “affect[ed] [themselves] in the capacity of a cook.”

Claypoole’s American Daily Advertiser (Philadelphia), Apr. 22, 1796

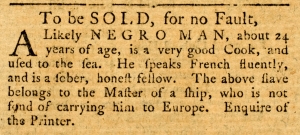

Although not all runaways seeking freedom at sea had prior cooking experience, many did. The prevalence of enslaved cooks in British American colonies is made evident by the scores of slave sale notices such as the one below. Having spent much time cooking for white masters fugitives found that those same skills could serve as the key to finding freedom at sea.

The Royal Gazette (New York), Feb. 6, 1779

George Prince, Jack Rogers and scores of other blacks served as cooks on African slaving ships. Other blacks, such as the itinerant preacher John Jea, worked as cooks on New England coasting vessels, trans-Atlantic merchant ships, Continental naval vessels, whaling ships, privateers, pirate ships, Lord Nelson’s naval ships and West Indies sloops. The narrative of the most famous 18th century black mariner, Olaudah Equiano, makes evident black cooks’ presence at sea. A quick perusal of Equiano’s Interesting Narrative (http://www.gutenberg.org/files/15399/15399-h/15399-h.htm) not only offers readers a description of a black ship cook spilling hot fat, but also tells of his friend John Amis, a cook on a West Indies ship, having been kidnapped in England and forcibly re-enslaved on the island of St. Kitts. In short, black cooks were ubiquitous in the 18th century Atlantic.

Mystic Seaport’s listing of The Charles W. Morgan‘s thirty-seven crews contains no identifiable blacks among the sixteen cooks in the ship’s crew lists serving between 1841 and 1921. However, as the Boston Globe recently reported, on the ship’s 37th voyage in 1921 the black Julian Grace served as the ship’s cook (the crew list does not indicate a cook for this voyage) http://www.bostonglobe.com/metro/2014/07/20/charles-morgan-brings-history-life-for-family-whose-roots-america-began-ship/oqPs97CwWWUjjbmVPKNTjI/story.html. Like a considerable number of other seamen on the Charles W. Morgan, Grace was from the Cape Verde Islands. Leaving Cape Verde at the age of nineteen Julian Grace settled in Massachusetts. His recipes for codfish cakes and beans with salted pork are still used by Grace family. Beans with salted pork would have been a meal Julian would have likely made for the Morgan‘s crew. But was he able to make them cachupa, the famous Cape Verde stew of slow cooked stew of corn, beans, and fish or meat ? Given that the ships of this era generally carried meat and often fished the basic elements of the stew would have been available to Grace (see http://library.mysticseaport.org/initiative/PageImage.cfm?PageNum=21&BibID=36681 for an example of the crew fishing). Was he able to bring on board the yams and plantains traditionally included in the stew? And did the ship’s provisions include the garlic and bay leaves that gives the dish its flavor? This is unlikely as few captains put much priority in spending monies to add variety to the crew’s meals. But other than an entry regarding making bread on board, the ship’s journal contains no reference to the ship’s cook (http://library.mysticseaport.org/initiative/PageImage.cfm?PageNum=38&BibID=36682) Thus what is unknown is how Julian’s, and for that matter, most Age of Sail cooks, cooking was received by his crewmates.

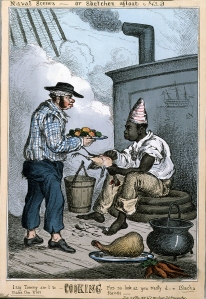

So eighteenth century cooks tended to be disabled, old and/or black. In short, they were often from the margins of society. It is therefore hardly surprising that in the eighteenth century black cooks often were ridiculed. Thomas McLean’s “Naval Scenes – or sketches afloat – No. 3 Cooking” is a good example such ridicule. Unlike the typical image of a black seaman during the Age of Sail that depicted sable sailors as heroic (see, e.g., http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/6/68/Fall_of_Nelson.jpg depicting a black gunner on the deck of HMS Victory at the moment of Lord Nelson’s death), McLean shows the black cook and steward on the slaver Sandown as foolish. The cook’s low status is made clear by his being bare foot; while many plantation slaves in the Americas worked barefoot, seamen generally did not. On the other hand the steward is shown as perhaps slow or inefficient in his work, asking the cook “Tommy am I to make the Pies” to which the cook replies, “Pies no look Al you nasty d– Black.”

Naval Scenes – or sketches afloat – No. 3 Cooking, http://collections.rmg.co.uk/collections/objects/127866.html

Black cooks were also often made subjects of entertainment. For example, on a 1792 voyage to Cadiz the black cook of the brig Minerva was awoken and ordered to prepare breakfast for the crew. However, when he could not be found a half hour later it was assumed he had fallen overboard. However, two days later the cook was discovered “crawling out of a hole, he had secured to sleep in,” and “from which he was only roused by hunger.” The crew was said to have “had a fine laugh on the occasion, and the cook was afforded them much entertainment since that time.”

Given the importance seamen placed upon food cooks were often the focus of their colleagues’ attention, for better and worse. With limited authority to alter what was generally a dull and repetitive diet (which will be the focus on my next blog), cooks stood responsible for a crucial element in crews’ lives and therefore the anger of the crew when food did not meet expectations. For example, when a black cook dropped a plate on a slave ship the cook was flogged and had salt water and cayenne rubbed on his back. In contrast, in 1724 when the free black cook on Francis Spriggs’ pirate ship divided provisions equally, the crew responded “very merrily.” In sum, when combined with not being viewed by most sailors as skilled maritime workers, cooks occupied an ambiguous and difficult place on most 18th century ships.

So simply stated being a ship cook offered both freedom from enslavement and economic independence for many blacks, while at times the position also often served to reinforce blacks’ inferior status within the Anglo-America Atlantic.

If blacks regularly worked as ship cooks what foods did they cook? My next two posts will consider the foods typically cooked on ships and the outsized place turtles and turtle soup had in the diet of whaling seamen.