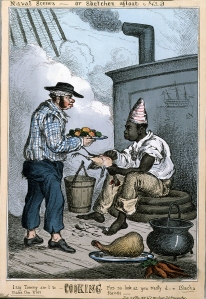

Today, on Martin Luther King Day, many Americans will recall the words from King’s famous 1963 March on Washington: “I have a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character.” Those words are often connected in our minds to images of water fountains with signs “White Only” or fire hoses being used against civil rights protest marchers. However, black Americans’ struggle for equality long predates the civil rights struggles of the 1960s. Today is an ideal time to briefly consider the struggles of black mariners in the early days of our nation’s history who did not always find themselves judged by “the content of their character,” but rather by “the color of their skin.”

As I have described in my article “Eighteenth Century ‘Prize Negroes’: From Britain to America,” Slavery & Abolition, 31:3 (Sept. 2010): 379-393, an implicit presumption in Admiralty Court procedures employed both by Great Britain and the United States up through the American Revolution was that captured enemy black seamen were slaves and therefore prize cargo. With the burden to prove otherwise too great for the vast majority of captured black sailors who found themselves far from friends and home, hundreds of free black mariners were condemned as prize goods and sold as slaves.

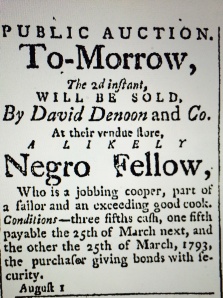

During the years after the Revolution increasing numbers of blacks could be found aboard American ships. While many of these men were free blacks from northern ports, southern planters (and some northern ship owners) continued to use enslaved seamen. Despite growing abolitionism and opposition to slavery black mariners’ travels through the Atlantic continued to be shaped by racism and hostility to their presence at sea. To illustrate this lets consider two black seamen who in the 1780s and 1790s worked for the Rhode Island merchant Welcome Arnold.

In the last three decades of the 18th century Welcome Arnold became prosperous through trans-Atlantic and coastal trading as well as ownership of a Providence distillery. Active in the fight to end the slave trade, Arnold regularly employed blacks in both his maritime and land-based businesses. During this time no less than eighty blacks served on Arnold’s ships. This Providence resident may have been unusual in the number of black seamen he employed, but other 18th century Ocean State merchants, such as the Brown family and Aaron Lopez, also consistently relied upon black tars.

The blacks employed by Arnold moved about the Atlantic, sailing to Amsterdam, Baltimore, Barbados, Cadiz, Cape Verde, Charleston, Copenhagen, Hamburg, Jamaica, Philadelphia, St. Martins, St. Petersburg, Surinam, Tobago, the Turks Islands and a score of other ports. One of these men, Sweet Luther, was able in just over three years, to rise from the rank of seamen to that of a mate on one of Arnold’s whaling ships. The large numbers of black seamen on Arnold’s ships, their ability to move about the Atlantic and Luther’s quick rise to officer status would seem to indicate acceptance of black sailors by white Rhode Islanders. However, black mariners’ lives were more complicated and difficult than these facts alone would have us conclude.

Luther stands out for as the only black who served as a steersman (harpooner), boatswain, mate or captain, on any of Arnold’s ships. This was hardly unusual. In my Black Mariner Database (“BMD”), a dataset containing information on more than 26,000 18th century black seamen and maritime fugitives, there are only a handful of blacks identified as officers. For example, some historians have characterized the British Royal Navy as being free of institutional racism. Whether the Royal Navy was or was not institutionally racist, black officers were rare in its crews. Among the 1300 identified black naval seamen in the BMD there are only seven officers. Nor did the Continental Navy promote blacks not into its officer ranks. Thus, although during the 18th century berths on ships offered blacks opportunities for meaningful employment often not available on land, progress up the maritime hierarchy was frequently very limited for most black seamen in the Atlantic.

The life of William Geltes, who served on Arnold’s ship the Minerva, is more illustrative of the limitations on opportunities for black seamen in the late 18th century.

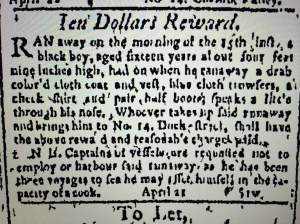

In 1796 Geltes clearly had reservations about going to sea. However, as it appears he was Welcome Arnold’s apprentice or indentured servant – Arnold paid a black employee of his for time Geltes boarded with the man – Geltes’ going to sea appears to have not been of his choosing. In December 1796 and again in February 1797 Geltes absented himself from the Minerva, for which he was docked $2.20. On February 4th, after having purchased a half-gallon of rum, perhaps to fortify his nerves during the long voyage to Charleston, St. Cadiz and St. Petersburg, Geltes fled the ship a third time. This time the Minerva’s captain was compelled to hire a “man going after him & fetching his cloathes.” Having been brought back to the ship, Geltes sailed south with it as a “raw hand” to Charleston, South Carolina. While the ship was in Charleston Geltes attempted to flee once again and found himself locked in the city’s workhouse for “correction.” In order for Geltes to be released the Minerva’s captain had to pay $37.64 in costs. Released and brought back on board Geltes “refused [his] duty.” For this Arnold docked Geltes’ wages $33.33 resulting, as in Limbo Robinson’s case, with the black sailor receiving no wages when he was discharged in Rhode Island.

Tomas Leitch, “View of Charles Town”

Geltes’ struggles were not necessarily due to his being black. Other servants and new seamen also found themselves harshly treated. But his voyage on the Minerva does serve as a vivid reminder of the difficulties many black men had in the early National era in establishing independent economic lives. In the 19th century these difficulties came to include significant legal restrictions on their movement.

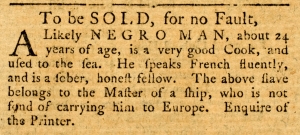

In response to Gabriel Vesey’s slave rebellion in which black sailors were believed to have assisted Vesey, South Carolina enacted the first Negro Seaman’s Act in 1822. The Act provided for the confinement of black mariners in the city’s jail until such time as the seamen’s ship left the port. An estimated 10,000 black seamen were imprisoned under Negro Seamen Acts. They included a free black New York sailor named Gilbert Horton who in 1826 was seized while walking the streets of the nation’s capital and thrown in jail and advertised to be a fugitive slave. Despite protests by ship captains, foreign diplomats and federal courts the imprisonment of black mariners continued throughout the antebellum era and occurred in a number of southern ports.

But whites’ concerns regarding black mariners spreading word of racial equality pre-dated Vesey’ Rebellion. In the aftermath of the Haitian Revolution fears in Charleston that a ship from St. Domingue, the Maria, with its “free negroes and people of color” would spread ideas of racial equality among the Palmeto State’s slaves caused local officials to refuse to allow the ship to land. Whites’ fears that free black mariners could destabilize their slave societies would continue until slavery ended. The result was that until the Thirteenth Amendment black seamen’s mobility and independence was remained subject to limitations imposed by southern state governments.